Reversing Towards

Josef Albers began his Structural Constellation series in 1949.

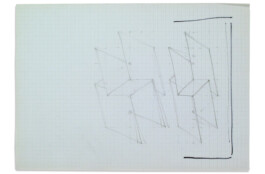

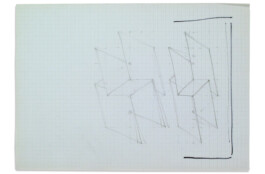

These two dimensional graphic works suggest a sequence of potential yet seemingly unstable objects.

Virtual planes simultæneously appear to extend and recede with implied depth.

Tangible resolutions fleetingly unify then dematerialise into ambiguity.

Each static monochrome representation holds multiple views.

Our internal thought and sensing of space are made visible.

It has long been asserted that Albers objects are illusory, contradictory and impossible.

To explore the limitations of this viewpoint we need to examine and understand the actual process of making.

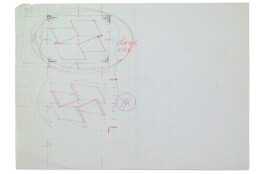

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation retains some 615 preliminary drawings and 57 related works made over two decades.

Many made whilst Josef and Anni were travelling in Mexico and Peru in the 1950’s.

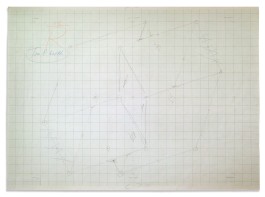

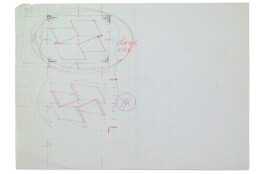

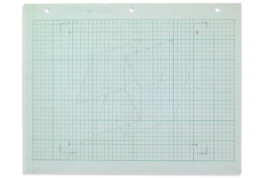

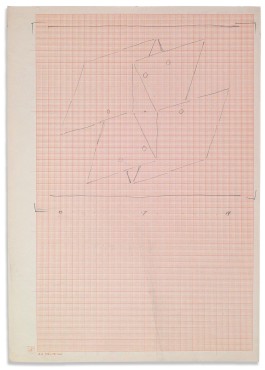

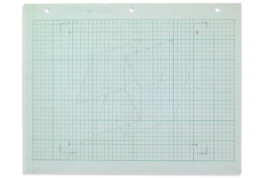

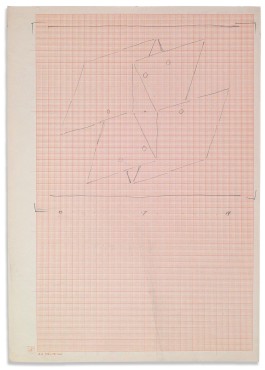

Most started out on commercial orange or green graph paper.

Dietzgen 'perfect cross section' engineering and surveying paper more often than not.

"For use by engineers on construction to transmit monthly progress of work by tracing from their field profile without having to do so much ruling."

Semi transparent drafting vellum for recording cartography and field measurements.

Cut sheets that could be conveniently traced with pencil on a chair or lap.

No allegiance to imperial or metric units just the underlying printed grid.

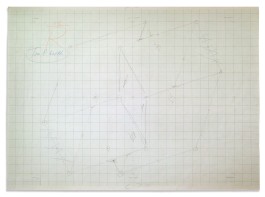

Feint pencil lines align tenuous connections and emergent unities are either underscored or suppressed.

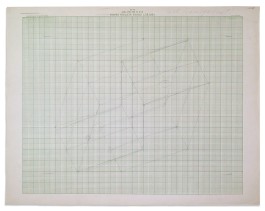

Standard projections are seemingly employed yet Albers generative process remains resolutely two dimensional.

Architectural or engineering drawing conventions locate and coordinate space within the certainty of a three dimensional matrix.

Unlike axonometric and isometric drawing Albers oblique projections of depth are not set at 45° or 30°.

He uses a far simpler dimetric technique of depiction termed 'cavalier' projection or sometimes high point view.

Formed with relaxed angles and consequently ambiguous distances between points.

Relatively easy to draw with pencil and ruler by hand and historically used to depict military fortifications.

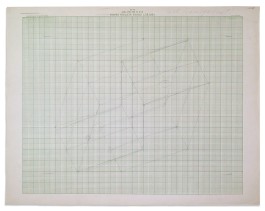

Albers Structural Constellations are not perspectives but parallel projections.

They lack a vanishing point and are only 'cavalier' in the sense the method casually possesses true scale in only two dimensions.

Albers never cheats the grid and consequently all of his compositions are coordinated by a Cartesian system.

Irrespective of the graph paper, precision survey sheet or dimestore pad to hand.

He rigorously ensures all his sketched lines coincided at points fixed precisely on the printed grid.

Without distortion or deception a hidden structure always provides the framework and disciplines all connections.

Pencil points are always nailed to the grid intersections never the space between.

Applying the same grid at 90 degrees allows us to determine the relative positions of the oblique points in space.

It also enablels us to reconstruct the connected planes and outline silhouettes prompted in the final artworks.

On this basis we can fully locate and construct Albers constellations in relative three dimensional space.

In the final reproductions, Albers delicately engraved his linear compositions into “Vinylite” plastic with a pantograph guided by the sketch templates.

The apparatus directed a simple stylus to replicate the compositions by cutting through the black vinyl laminate to expose the underlying material as a white line.

Transparent planes are occasionally hinted with glassy fills and notional edges sometimes underscored.

Yet Albers Structural Constellations embody representations of perfectly possible forms.

Beneath the black void all points still resolve meticulously back to Albers originating sketch paper grid.

His compositions are precisely coordinated in both length and breadth they just lack true depth.

Every aspect of the series is spatially located and vectored just extent remains undetermined.

The key to decrypt Albers seemingly paradoxical geometries lies in the graph paper used to generate them.

Despite the possibility, Albers had no intention of consolidating his images and making them explicit.

His constellations are left exquisitely unstructured, unresolved and determinedly open.

Our visual systems complete the experience by making inferences beyond the information presented.

The human brain seeking unity processes the configurations, points and lines into comprehensible surfaces and objects.

We have evolved to preferentially process three dimensional object inputs over two dimensional image content.

Presented with a map of the stars we summon mythological creatures, earthbound animals, patterns and the domestic objects of memory.

With kind permission of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

Collaborators

Nicholas Fox-Weber

Brenda Danilowitz

Samuel McCune

Anne Sisco

Wayne McGregor

Rebecca Marshall

Polly Hunt

Reversing Towards

Josef Albers began his Structural Constellation series in 1949.

These two dimensional graphic works suggest a sequence of potential yet seemingly unstable objects.

Virtual planes simultæneously appear to extend and recede with implied depth.

Tangible resolutions fleetingly unify then dematerialise into ambiguity.

Each static monochrome representation holds multiple views.

Our internal thought and sensing of space are made visible.

It has long been asserted that Albers objects are illusory, contradictory and impossible.

To explore the limitations of this viewpoint we need to examine and understand the actual process of making.

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation retains some 615 preliminary drawings and 57 related works made over two decades.

Many made whilst Josef and Anni were travelling in Mexico and Peru in the 1950’s.

Most started out on commercial orange or green graph paper.

Dietzgen 'perfect cross section' engineering and surveying paper more often than not.

"For use by engineers on construction to transmit monthly progress of work by tracing from their field profile without having to do so much ruling."

Semi transparent drafting vellum for recording cartography and field measurements.

Cut sheets that could be conveniently traced with pencil on a chair or lap.

No allegiance to imperial or metric units just the underlying printed grid.

Feint pencil lines align tenuous connections and emergent unities are either underscored or suppressed.

Standard projections are seemingly employed yet Albers generative process remains resolutely two dimensional.

Architectural or engineering drawing conventions locate and coordinate space within the certainty of a three dimensional matrix.

Unlike axonometric and isometric drawing Albers oblique projections of depth are not set at 45° or 30°.

He uses a far simpler dimetric technique of depiction termed 'cavalier' projection or sometimes high point view.

Formed with relaxed angles and consequently ambiguous distances between points.

Relatively easy to draw with pencil and ruler by hand and historically used to depict military fortifications.

Albers Structural Constellations are not perspectives but parallel projections.

They lack a vanishing point and are only 'cavalier' in the sense the method casually possesses true scale in only two dimensions.

Albers never cheats the grid and consequently all of his compositions are coordinated by a Cartesian system.

Irrespective of the graph paper, precision survey sheet or dimestore pad to hand.

He rigorously ensures all his sketched lines coincided at points fixed precisely on the printed grid.

Without distortion or deception a hidden structure always provides the framework and disciplines all connections.

Pencil points are always nailed to the grid intersections never the space between.

Applying the same grid at 90 degrees allows us to determine the relative positions of the oblique points in space.

It also enablels us to reconstruct the connected planes and outline silhouettes prompted in the final artworks.

On this basis we can fully locate and construct Albers constellations in relative three dimensional space.

In the final reproductions, Albers delicately engraved his linear compositions into “Vinylite” plastic with a pantograph guided by the sketch templates.

The apparatus directed a simple stylus to replicate the compositions by cutting through the black vinyl laminate to expose the underlying material as a white line.

Transparent planes are occasionally hinted with glassy fills and notional edges sometimes underscored.

Yet Albers Structural Constellations embody representations of perfectly possible forms.

Beneath the black void all points still resolve meticulously back to Albers originating sketch paper grid.

His compositions are precisely coordinated in both length and breadth they just lack true depth.

Every aspect of the series is spatially located and vectored just extent remains undetermined.

The key to decrypt Albers seemingly paradoxical geometries lies in the graph paper used to generate them.

Despite the possibility, Albers had no intention of consolidating his images and making them explicit.

His constellations are left exquisitely unstructured, unresolved and determinedly open.

Our visual systems complete the experience by making inferences beyond the information presented.

The human brain seeking unity processes the configurations, points and lines into comprehensible surfaces and objects.

We have evolved to preferentially process three dimensional object inputs over two dimensional image content.

Presented with a map of the stars we summon mythological creatures, earthbound animals, patterns and the domestic objects of memory.

With kind permission of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

Collaborators

Nicholas Fox-Weber

Brenda Danilowitz

Samuel McCune

Anne Sisco

Wayne McGregor

Rebecca Marshall

Polly Hunt